When it comes to applications intended to last, I think we all want to have simple code that's easier to maintain. Where we often really disagree is how to accomplish that. In this blog post I'm going to talk about how I see functions, objects, and classes fitting into that discussion.

A class

Let's take a look at an example of a class implementation to illustrate my point:

class Person {

constructor(name) {

// common convention is to prefix properties with `_`

// if they're not supposed to be used. See the appendix

// if you want to see an alternative

this._name = name

this.greeting = 'Hey there!'

}

setName(strName) {

this._name = strName

}

getName() {

return this._getPrefixedName('Name')

}

getGreetingCallback() {

const { greeting, _name } = this

return (subject) => `${greeting} ${subject}, I'm ${_name}`

}

_getPrefixedName(prefix) {

return `${prefix}: ${this._name}`

}

}

const person = new Person('Jane Doe')

person.setName('Sarah Doe')

person.greeting = 'Hello'

person.getName() // Name: Sarah Doe

person.getGreetingCallback()('Jeff') // Hello Jeff, I'm Sarah Doe

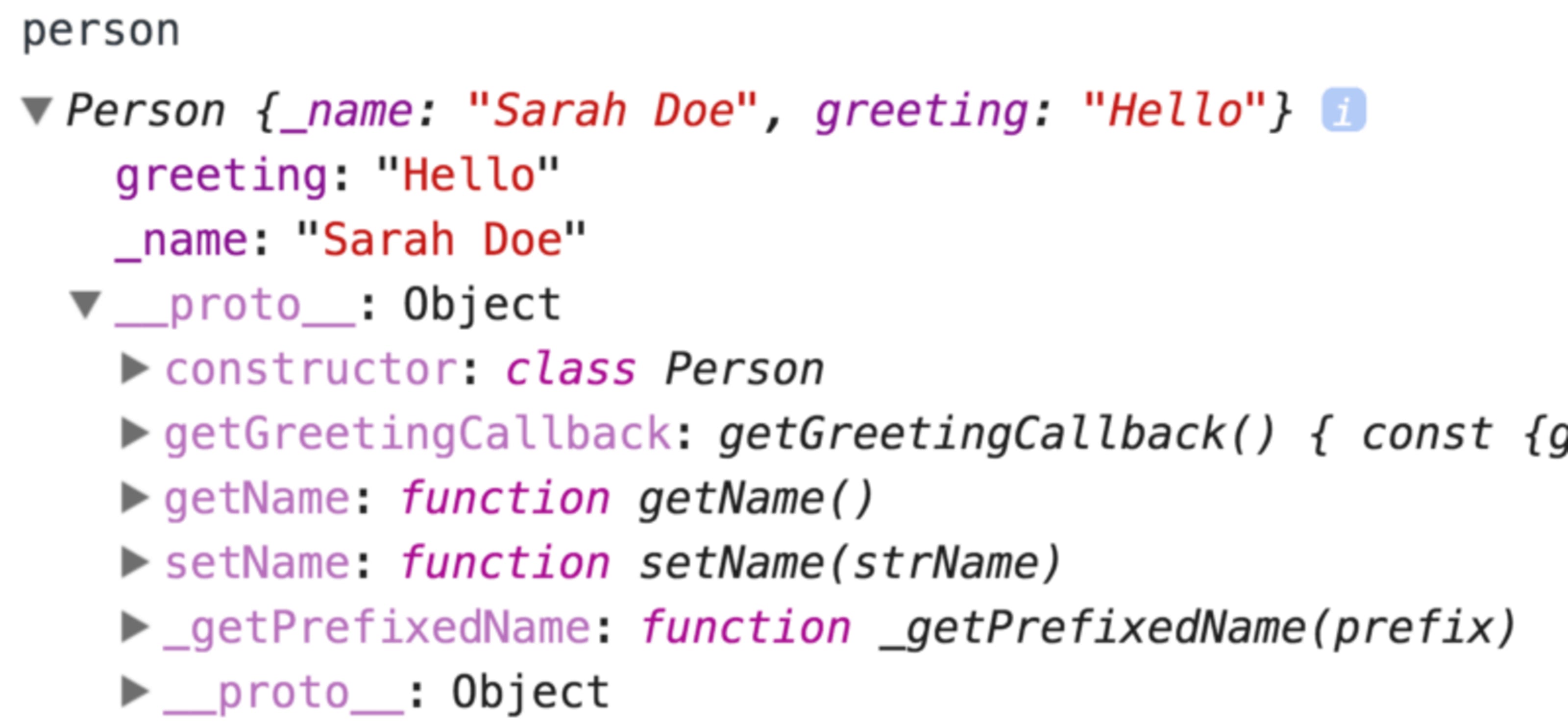

So we've declared a Person class with a constructor instantiating a few member

properties as well as a couple of methods. With that, if we type out the

person object in the Chrome console, it looks like this:

The real benefit to notice here is that most of the properties for this person

live on the prototype (shown as __proto__ in the screenshot) rather than the

instance of person. This is not insignificant because if we had ten thousand

instances of person they would all be able to share a reference to the same

methods rather than having ten thousand copies of those methods everywhere.

What I want to focus on now is how many concepts you have to learn to really understand this code and how much complexity those concepts add to your code.

- Objects: Pretty basic. Definitely entry level stuff here. They don't add a whole lot of complexity by themselves.

- Functions (and closures): This is also pretty fundamental to the language. Closures do add a bit of complexity to your code (and can cause problems if you're not careful), but you really can't make it too far in JavaScript without having to learn these. (Learn more here).

- A function/method's

thiskeyword: Definitely an important concept in JavaScript.

My assertion is that this is hard to learn and can add unnecessary

complexity to your codebase.

The this keyword

Here's what

MDN

has to say about this:

A function's

thiskeyword behaves a little differently in JavaScript compared to other languages. It also has some differences between strict mode and non-strict mode.

In most cases, the value of

thisis determined by how a function is called. It can't be set by assignment during execution, and it may be different each time the function is called. ES5 introduced thebindmethod to set the value of a function's >this> regardless of how it's called, and ES2015 introduced arrow functions whosethisis lexically scoped (it is set to thethisvalue of the enclosing execution context).

Maybe not rocket science 🚀, but it's an implicit relationship and it's

definitely more complicated than just objects and closures. You can't get away

from objects and closures, but I believe you can often get away with avoiding

classes and this most of the time.

Here's a (contrived) example of where things can break down with this.

const person = new Person('Jane Doe')

const getGreeting = person.getGreeting

// later...

getGreeting() // Uncaught TypeError: Cannot read property 'greeting' of undefined at getGreeting

The core issue is that your function has been

"complected" with wherever it is referenced

because it uses this.

For a more real world example of the problem, you'll find that this is especially evident in React ⚛️. If you've used React for a while, you've probably made this mistake before as I have:

class Counter extends React.Component {

state = { clicks: 0 }

increment() {

this.setState({ clicks: this.state.clicks + 1 })

}

render() {

return (

<button onClick={this.increment}>

You have clicked me {this.state.clicks} times

</button>

)

}

}

When you click the button you'll see:

Uncaught TypeError: Cannot read property 'setState' of null at increment

And this is all because of this, because we're passing it to onClick which

is not calling our increment function with this bound to our instance of the

component. There are various ways to fix this

(watch this free 🆓 egghead.io video 💻 about how).

The fact that you have to think about this adds cognitive load that would be

nice to avoid.

How to avoid this

So, if this adds so much complexity (as I'm asserting), how do we avoid it

without adding even more complexity to our code? How about instead of the

object-oriented approach of classes, we try a more functional approach? This is

how things would look if we used

pure functions:

function setName(person, strName) {

return Object.assign({}, person, { name: strName })

}

// bonus function!

function setGreeting(person, newGreeting) {

return Object.assign({}, person, { greeting: newGreeting })

}

function getName(person) {

return getPrefixedName('Name', person.name)

}

function getPrefixedName(prefix, name) {

return `${prefix}: ${name}`

}

function getGreetingCallback(person) {

const { greeting, name } = person

return (subject) => `${greeting} ${subject}, I'm ${name}`

}

const person = { greeting: 'Hey there!', name: 'Jane Doe' }

const person2 = setName(person, 'Sarah Doe')

const person3 = setGreeting(person2, 'Hello')

getName(person3) // Name: Sarah Doe

getGreetingCallback(person3)('Jeff') // Hello Jeff, I'm Sarah Doe

With this solution we have no reference to this. We don't have to think about

it. As a result, it's easier to understand. Just functions and objects. There is

basically no state you need to keep in your head at all with these functions

which makes it very nice! And the person object is just data, so even easier to

think about:

Another nice property of functional programming that I won't delve into very far is that it's very easy to unit test. You simply call a function with some input and assert on its output. You don't need to set up any state beforehand. That's a very handy property!

Note that functional programming is more about making code easier to understand

so long as it's "fast enough." Despite speed of execution not being the focus,

there are some reeeeally nice perf wins you can get in certain scenarios (like

reliable === equality checks for objects for example). More often than not,

your use of functional programming will often be way down on the list of

bottlenecks that are making your application slow.

Cost and Benefit

Usage of class is not bad. It definitely has its place. If you have some

really

"hot" code

that's a bottleneck for your application, then using class can really speed

things up. But 99% of the time, that's not the case. And I don't see how

classes and the added complexity of this is worth it for most cases (let's

not even get started with

prototypal inheritance).

I have yet to have a situation where I needed classes for performance. So I

only use them for React components because that's what you have to do if you

need to use state/lifecycle methods (but maybe not in the

future).

Conclusion

Classes (and prototypes) have their place in JavaScript. But they're an optimization. They don't make your code simpler, they make it more complex. It's better to narrow your focus on things that are not only simple to learn but simple to understand: functions and objects.

See you around friends!

Appendix

Here are a few extras for your viewing pleasure :)

The Module Pattern

Another way to avoid the complexities of this and leverages simple objects and

functions is the Module pattern. You can learn more about this pattern from

Addy Osmani's

“Learning JavaScript Design Patterns”

book which is available to read for free

here.

Here's an implementation of our person class based on Addy's

“Revealing Module Pattern”:

function getPerson(initialName) {

let name = initialName

const person = {

setName(strName) {

name = strName

},

greeting: 'Hey there!',

getName() {

return getPrefixedName('Name')

},

getGreetingCallback() {

const { greeting } = person

return (subject) => `${greeting} ${subject}, I'm ${name}`

},

}

function getPrefixedName(prefix) {

return `${prefix}: ${name}`

}

return person

}

const person = getPerson('Jane Doe')

person.setName('Sarah Doe')

person.greeting = 'Hello'

person.getName() // Name: Sarah Doe

person.getGreetingCallback()('Jeff') // Hello Jeff, I'm Sarah Doe

What I love about this is that there are few concepts to understand. We have a function which creates a few variables and returns an object — simple. Pretty much just objects and functions. For reference, this is what the person object looks like if you expand it in Chrome DevTools:

Just an object with a few properties.

One of the flaws of the module pattern above is that every person has its very

own copy of each property and function For example:

const person1 = getPerson('Jane Doe')

const person2 = getPerson('Jane Doe')

person1.getGreetingCallback === person2.getGreetingCallback // false

Even though the contents of the getGreetingCallback function are identical,

they will each have their own copy of that function in memory. Most of the time

this doesn't matter, but if you're planning on making a ton of instances of

these, or you want creating these to be more than fast, this can be a bit of a

problem. With our Person class, every instance we create will have a reference

to the exact same method getGreetingCallback:

const person1 = new Person('Jane Doe')

const person2 = new Person('Jane Doe')

person1.getGreetingCallback === person2.getGreetingCallback // true

// and to take it a tiny bit further, these are also both true:

person1.getGreetingCallback === Person.prototype.getGreetingCallback

person2.getGreetingCallback === Person.prototype.getGreetingCallback

The nice thing with the module pattern is that it avoids the issues with the callsite we saw above.

const person = getPerson('Jane Doe')

const getGreeting = person.getGreeting

// later...

getGreeting() // Hello Jane Doe

We don't need to concern ourselves with this at all in that case. And there

are other issues

with relying heavily on closures to be aware of. It's all about trade-offs.

Private properties with classes

If you really do want to use class and have private capabilities of closures,

then you may be interested in

this proposal (currently

stage-2, but unfortunately no babel support

yet):

class Person {

#name

greeting = 'hey there'

#getPrefixedName = prefix => `${prefix}: ${this.#name}`

constructor(name) {

this.#name = name

}

setName(strName) {

#name = strName

// look at this! shorthand for:

// this.#name = strName

}

getName() {

return #getPrefixedName('Name')

}

getGreetingCallback() {

const {greeting} = this

return subject => `${this.greeting} ${subject}, I'm ${#name}`

}

}

const person = new Person('Jane Doe')

person.setName('Sarah Doe')

person.greeting = 'Hello'

person.getName() // Name: Sarah Doe

person.getGreetingCallback()('John') // Hello John, I'm Sarah Doe

person.#name // undefined or error or something... Either way it's totally inaccessible!

person.#getPrefixedName // same as above. Woo! 🎊 🎉

So we've got the solution to the privacy problem with that proposal. However it

doesn't rid us of the complexities of this, so I'll likely only use this in

places where I really need performance gains of class.

I should also note that you can use a WeakMap to get privacy for classes as well, like I demonstrate in the WeakMap exercises in the es6–workshop.

Additional Reading

This article by Tyler McGinnis called “Object Creation in JavaScript” is a terrific read.

If you want to learn about functional programming, I highly suggest “The Mostly Adequate Guide to Functional Programming” by Brian Lonsdorf, and (for those of you with a Frontend Masters subscription) “Functional-Lite JavaScript” by Kyle Simpson.