I was preparing a blog post on a subject related to React re-renders when I stumbled upon this little React gem of knowledge I think you'll really appreciate:

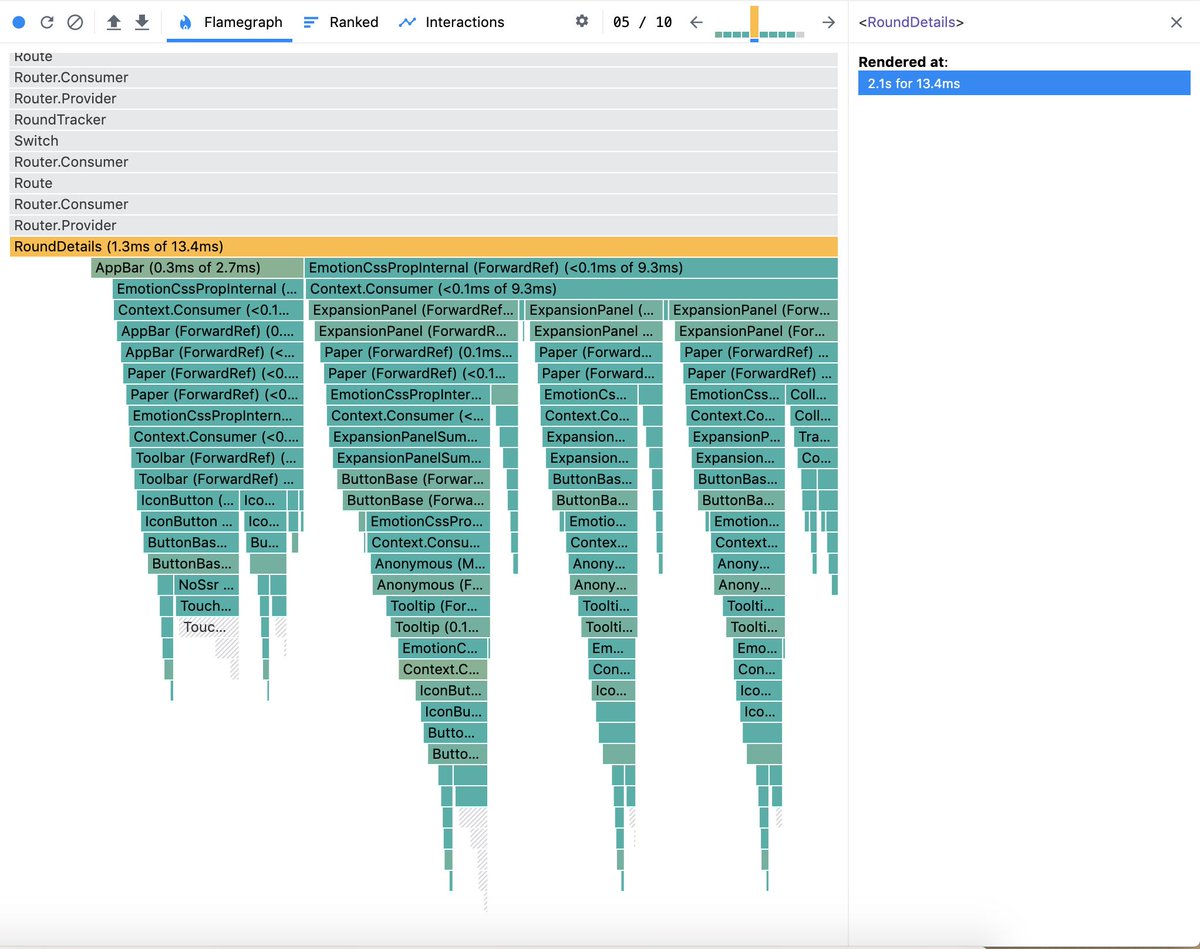

After reading this blog post, Brooks Lybrand implemented this trick and this was the result:

Excited? Let's break it down with a simple contrived example and then talk about what practical application this has for you in your day-to-day apps.

An example

// play with this on codesandbox: https://codesandbox.io/s/react-codesandbox-g9mt5

import * as React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'

function Logger(props) {

console.log(`${props.label} rendered`)

return null // what is returned here is irrelevant...

}

function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = React.useState(0)

const increment = () => setCount((c) => c + 1)

return (

<div>

<button onClick={increment}>The count is {count}</button>

<Logger label="counter" />

</div>

)

}

ReactDOM.render(<Counter />, document.getElementById('root'))

When that's run, "counter rendered" will be logged to the console initially, and each time the count is incremented, "counter rendered" will be logged to the console. This happens because when the button is clicked, state changes and React needs to get the new React elements to render based on that state change. When it gets those new elements, it renders and commits them to the DOM.

Here's where things get interesting. Consider the fact that

<Logger label="counter" /> never changes between renders. It's static, and

therefore could be extracted. Let's try that just for fun (I'm not recommending

you do this, wait for later in the blog post for practical recommendations).

// play with this on codesandbox: https://codesandbox.io/s/react-codesandbox-o9e9f

import * as React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'

function Logger(props) {

console.log(`${props.label} rendered`)

return null // what is returned here is irrelevant...

}

function Counter(props) {

const [count, setCount] = React.useState(0)

const increment = () => setCount((c) => c + 1)

return (

<div>

<button onClick={increment}>The count is {count}</button>

{props.logger}

</div>

)

}

ReactDOM.render(

<Counter logger={<Logger label="counter" />} />,

document.getElementById('root'),

)

Did you notice the change? Yeah! We get the initial log, but then we don't get new logs when we click the button anymore! WHAAAAT!?

If you want to skip all the deep-dive technical details and get to the "what does this mean for me" go ahead and plop yourself down there now

What's going on?

So what's causing this difference? Well, it has to do with React elements. Why don't you take a quick break and read my blog post "What is JSX?" to get a quick refresher on React elements and their relationship to JSX.

When React calls the counter function, it gets back something that looks a bit like this:

// some things removed for clarity

const counterElement = {

type: 'div',

props: {

children: [

{

type: 'button',

props: {

onClick: increment, // this is the click handler function

children: 'The count is 0',

},

},

{

type: Logger, // this is our logger component function

props: {

label: 'counter',

},

},

],

},

}

These are called UI descriptor objects. They describe the UI that React should create in the DOM (or via native components for react native). Let's click the button and take a look at the changes:

const counterElement = {

type: 'div',

props: {

children: [

{

type: 'button',

props: {

onClick: increment,

children: 'The count is 1',

},

},

{

type: Logger,

props: {

label: 'counter',

},

},

],

},

}

As far as we can tell, the only changes are the onClick and children props

of the button element. However, the entire thing is completely new! Since the

dawn of time using React, you've been creating these objects brand new on every

render. (Luckily, even mobile browsers are pretty fast at this, so that has

never been a significant performance problem).

It may actually be easier to investigate at the parts of this tree of React elements is the same between renders, so here are the things that did NOT change between those two renders:

const counterElement = {

type: 'div',

props: {

children: [

{

type: 'button',

props: {

onClick: increment,

children: 'The count is 1',

},

},

{

type: Logger,

props: {

label: 'counter',

},

},

],

},

}

All the element types are the same (this is typical), and the label prop for

the Logger element is unchanged. However the props object itself changes every

render, even though the properties of that object are the same as the previous

props object.

Ok, here's the kicker right here. Because the Logger props object has changed, React needs to re-run the Logger function to make sure that it doesn't get any new JSX based on the new props object (in addition to effects that may need to be run based on the props change). But what if we could prevent the props from changing between renders? If the props don't change, then React knows that our effects shouldn't need to be re-run and our JSX shouldn't change (because React relies on the fact that our render methods should be idempotent). This is exactly what React is coded to do right here and it's been that way since React first started!

Ok, but the problem is that

react creates a brand new props object every time we create a React element,

so how do we ensure that the props object doesn't change between renders?

Hopefully now you've got it and you understand why the second example above

wasn't re-rendering the Logger. If we create the JSX element once and re-use

that same one, then we'll get the same JSX every time!

Let's bring it back together

Here's the second example again (so you don't have to scroll back up):

// play with this on codesandbox: https://codesandbox.io/s/react-codesandbox-o9e9f

import * as React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom'

function Logger(props) {

console.log(`${props.label} rendered`)

return null // what is returned here is irrelevant...

}

function Counter(props) {

const [count, setCount] = React.useState(0)

const increment = () => setCount((c) => c + 1)

return (

<div>

<button onClick={increment}>The count is {count}</button>

{props.logger}

</div>

)

}

ReactDOM.render(

<Counter logger={<Logger label="counter" />} />,

document.getElementById('root'),

)

So let's checkout the things that are the same between renders:

const counterElement = {

type: 'div',

props: {

children: [

{

type: 'button',

props: {

onClick: increment,

children: 'The count is 1',

},

},

{

type: Logger,

props: {

label: 'counter',

},

},

],

},

}

Because the Logger element is completely unchanged (and therefore the props are

unchanged as well), React can automatically provide this optimization for us and

not bother re-rendering the Logger element because it shouldn't need to be

re-rendered anyway. This is basically like React.memo except instead of

checking each of the props individually, React is checking the props object

holistically.

So what does this mean for me?

In summary, if you're experiencing performance issues, try this:

- "Lift" the expensive component to a parent where it will be rendered less often.

- Then pass the expensive component down as a prop.

You may find doing so solves your performance problem without needing to spread

React.memo all over you codebase like a giant intrusive band-aid 🤕😉

Demo

Creating a practical demo of a slow app in React is tricky because it kinda requires building a full app, but I do have a contrived example app that has a before/after that you can check out and play with:

One thing I want to add is that even though it's better to use the faster version of this code, it's still performing really badly when it renders initially and it would perform really badly if it ever actually needed to do another top-down re-render (or when you update the rows/columns). That's a performance problem that should probably be dealt with on its own merits (irrespective of how necessary the re-renders are). Also please remember that codesandbox uses the development version of React which gives you a really nice development experience, but performs WAY slower than the production version of React.

And this isn't just something that's useful at the top-level of your app either. This could be applied to your app anywhere it makes sense. What I like about this is that "It's both natural for composition and acts as an optimization opportunity." (that was Dan). So I do this naturally and get the perf benefits for free. And that's what I've always loved about React. React is written so that idiomatic React apps are fast by default, and then React provides optimization helpers for you to use as escape hatches.

Good luck!

I want to add a note that if you're using legacy context, you wont be able to get this optimization, as React has a special case for that here, so people concerned about performance should probably migrate from legacy context.